Why do my gums bleed?

An introduction to periodontal disease!

An introduction to periodontal disease

Periodontal disease is simply defined as: "Perio" = around + "dontal" = teeth → disease around the teeth.

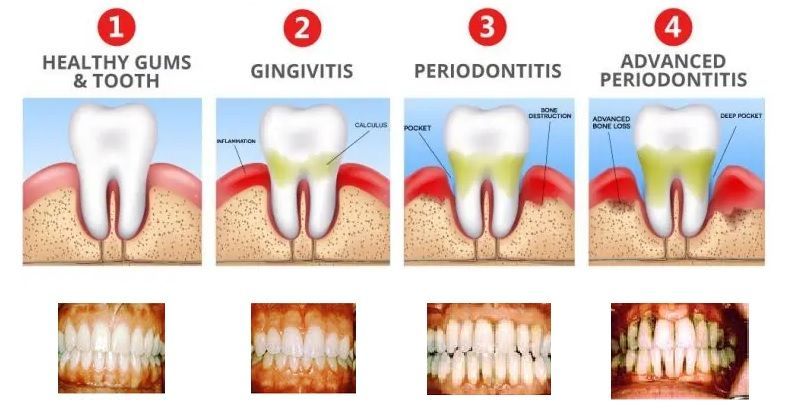

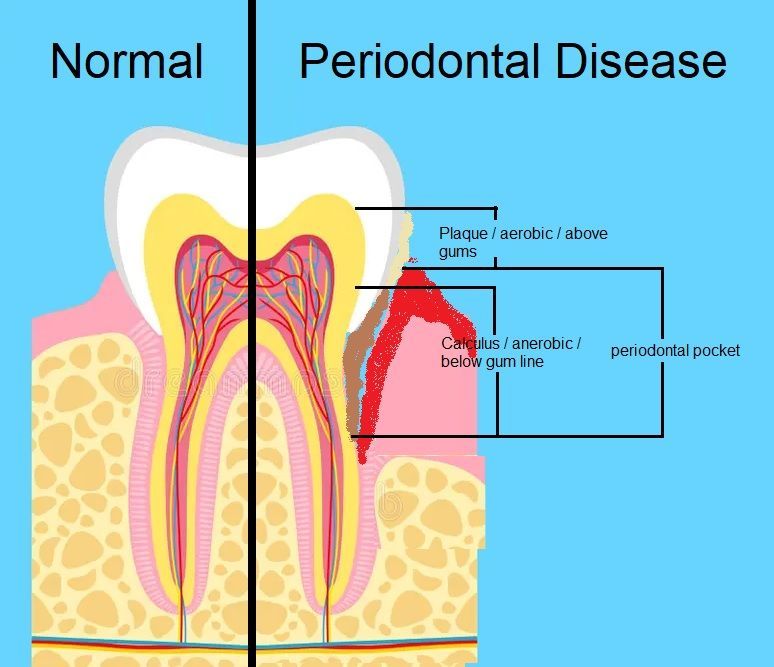

How plaque and gingivitis progresses into calculus and periodontal disease

How does plaque lead to gingivitis?

Periodontal disease is simply defined as: "Perio" = around + "dontal" = teeth → disease around the teeth.Bacteria are always present in the mouth and survive by clinging to the teeth using sticky proteins. They multiply and form goo-like colonies called plaque. These bacteria feed on the food and drinks we consume—especially high-carbohydrate diets, which fuel rapid plaque growth. If left undisturbed, plaque builds up around the gumline and between teeth below contact areas. This leads to gingivitis, an early-stage infection where the gums become inflamed and bleed easily. Gingivitis, or inflamed gums, is reversible with proper brushing and flossing. At this stage, the condition is not considered a serious problem if treated promptly.

How does calculus lead to periodontal disease?

when plaque is left in place, it hardens (mineralizes) into calculus. Calculus cannot be removed by brushing or flossing. It must be professionally scraped off. The process of plaque turning into calculus happens alongside the body’s natural mechanism to protect teeth—remineralization. After eating acidic foods (pH below 5.5) tooth enamel demeralizes, the parotid and submandibular salivary glands secrete saliva rich in calcium and phosphate, which rebuilds enamel (made of hydroxyapatite and collagen). Unfortunately, this same mineral-rich saliva also calcifies plaque into hardened calculus.

If calculus remains on the teeth, bacterial colonies continue to grow and become larger and more deeply embedded, traveling down the sides of the teeth. The gums remain chronically inflamed and start to pull away from the calculus, creating a pathway for deeper bacterial invasion down the tooth root. These bacteria then destroy the ligaments and connective fibers that attach the teeth to the bone, leading to bone loss and the formation of periodontal pockets. At this point, the condition is defined as

periodontal disease.

How is periodontal disease assesed?

Its severity is measured by pocket depth and bone loss:

- 4 mm pockets indicate mild disease

- 4–5 mm pockets indicate moderate disease

- 6 mm or greater indicates severe disease

Pockets of 4 mm or greater cannot be effectively cleaned with a toothbrush or floss and typically require surgical intervention. As the disease advances, bone loss continues, the attachment structures deteriorate, pocket depths increase, gums easily bleed from inflamation, and teeth become loose in their sockets.

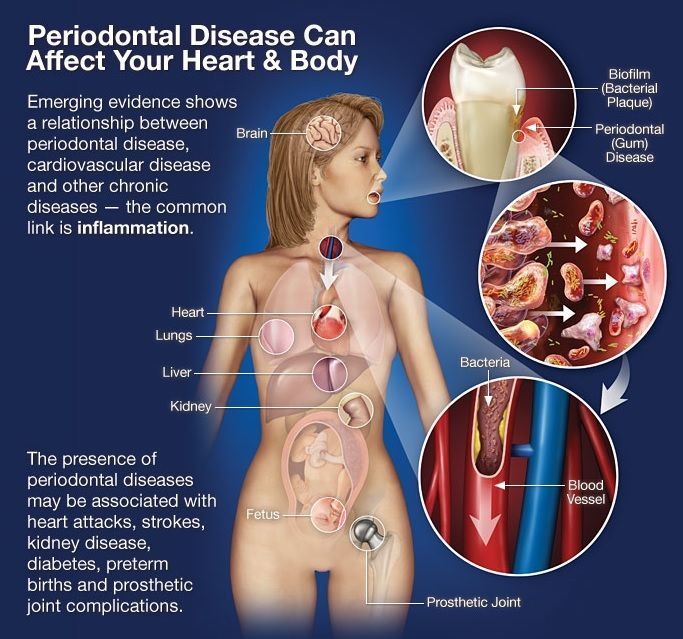

Why is periodontal disease dangerous?

To contain the infection, blood vessels in the socket expand to allow white blood cells to flood the area—part of the body’s natural immune response. However, despite the effort, the infection persists. Pus begins to form from the inflammatory process and may drain from the affected area, often without any pain. Pain typically arises in the later stages of the disease, when periodontal abscesses form.

Abscesses are pus-filled blisters of dead white blood cells, that develop when the immune system becomes locally overwhelmed and can no longer contain the infection.

As blood vessels open to allow immune cells into the site, bacteria may enter the bloodstream. This can lead to a serious condition called septicemia—a systemic, traveling bacterial infection. These bacteria are especially dangerous because they thrive in low-oxygen environments like blood vessels, heart valves, and internal organs. In chronic cases, particularly among the elderly or immunocompromised, this can cause irreversible damage or even death.

One well-known and serious complication of periodontal disease is bacterial endocarditis—an infection where oral bacteria colonize and destroy heart valves. This condition has been directly linked to periodontal bacteria entering the bloodstream.

Aerobic vs. Anaerobic Bacteria in Periodontal Disease

There are two types of bacteria involved:

- Aerobic bacteria are found above the gumline in gingivitis. They require oxygen and feed on food you eat. While they contribute to plaque formation, they are generally less harmful.

- Anaerobic bacteria live where oxygen is scarce in periodontis. These bacteria are far more destructive. They do not feed on your food—they feed on you. They consume periodontal tissues and use sticky proteins to cling not just to the tooth surface, but to your tissue as well like heart valves, blood vessels, and organ cavities via septicemia.

Note in the chart below: Bacteria associated with Gingivitis are mostly aerobic verses Periodontis which are mostly anaerobic

| Bacterium | Associated Condition | Gram Stain | Oxygen Requirement | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptococcus sanguinis | Gingivitis | Gram-positive | Aerobic | Early colonizer; helps prevent pathogen overgrowth |

| Actinomyces species | Gingivitis | Gram-positive | Aerobic | Found in early plaque; linked to mild inflammation |

| Capnocytophaga species | Gingivitis | Gram-negative | Aerobic | Common in gingival crevice flora |

| Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans | Periodontitis | Gram-negative | Aerobic | Major role in aggressive periodontitis |

| Eikenella corrodens | Periodontitis | Gram-negative | Aerobic | Transitional flora between gingivitis & periodontitis |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | Both | Gram-negative | Anaerobic | Bridge species for biofilm development |

| Prevotella intermedia | Periodontitis | Gram-negative | Anaerobic | Associated with deep periodontal pockets |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | Periodontitis | Gram-negative | Anaerobic | Keystone pathogen in chronic periodontitis |

| Tannerella forsythia | Periodontitis | Gram-negative | Anaerobic | Found in severe periodontitis |

| Treponema denticola | Periodontitis | Gram-negative spirochete | Anaerobic | Motile; highly destructive in late-stage disease |

🦠 Overlapping Bacteria: Periodontal Disease & Endocarditis

note they are moslty ANAEROBIC!

| Bacterium | Gram | Oxygen Type | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans | Gram-negative | Facultative anaerobe | Aggressive periodontitis; culture-negative endocarditis (HACEK) |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | Gram-negative | Anaerobic | Dental biofilms; rare endocarditis cases |

| Eikenella corrodens | Gram-negative | Facultative anaerobe | Periodontal flora; HACEK endocarditis |

| Streptococcus sanguinis | Gram-positive | Facultative anaerobe | Plaque colonizer; major cause of subacute endocarditis |

| Streptococcus mitis/oralis | Gram-positive | Facultative anaerobe | Normal oral flora; linked to endocarditis in at-risk patients |

What are the 3 early signs of periodontal disease?

- bleeding gums

- bad breath

- swelling gums

Take this short quiz to determine your periodontal health.

Top 20 Periodontal Disease Questions

What People Say About Us!